The Baja California Peninsula, a slender strip of land bordered by the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California, stretches over 1,200 miles from Mexicali in the north to Cabo San Lucas in the south, featuring rugged mountain ranges, arid deserts, vibrant mangroves and lush oases. While well known for its captivating landscapes, what’s perhaps more fascinating is the story of its origin—a story written in the language of tectonic plate movements, over tens of millions of years.

This process is linked to the activity of the San Andreas Fault and other associated fault systems, which collectively form a boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. The movement of these tectonic plates is a slow but relentless process, occurring over millions of years. (Slow, and yet we’ve documented quite a bit of movement over that long period of time).

The Pacific Plate is moving northwest relative to the North American Plate, and the San Andreas Fault system primarily accommodates this movement. In essence, the Baja California Peninsula is moving with the Pacific Plate alongside and away from the North American Plate.

The separation is taking place at an average rate of about 2 to 5 centimeters per year. Over millions of years, these movements accumulate, leading to significant shifts in the geography of regions like Baja California. According to geologists, within the next 20-30 million years, this tectonic movement will eventually break Baja and the westernmost part of California off of North America. Some geologists speculate that Baja California and parts of Southern California could eventually break off from the mainland entirely and become an island.

The movement of the continental crust in the area is due in part to seafloor spreading at a massive seam that stretches across the earth. Called the East Pacific Rise, the seam stretches from the southeastern Pacific Ocean towards Antarctica, to the Gulf of California, essentially right to the mouth of the Colorado River.

Some 30 million years ago, during the late Oligocene epoch, the southwestern edge of North America appeared quite different than it does today. The area now occupied by the Baja California Peninsula was attached to mainland Mexico, and the Sea of Cortez didn’t exist. The Pacific and North American tectonic plates were grinding against each other along a convergent boundary, a zone where plates come together, and one often slides beneath the other—a process known as subduction.

But the story of Baja California’s tectonic journey is not just about earthquakes and ecosystems. It’s also a story of water. The Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez, which separates the peninsula from the mainland, is a young sea, geologically speaking. It formed as the peninsula began to pull away, a process that continues to this day. This body of water is a critical habitat for marine life, including several species of whales and dolphins that depend on its warm waters. Jacques Cousteau, the famous French oceanographer, famously referred to the Gulf of California as “the world’s aquarium” due to its vast array of (declining) marine life.

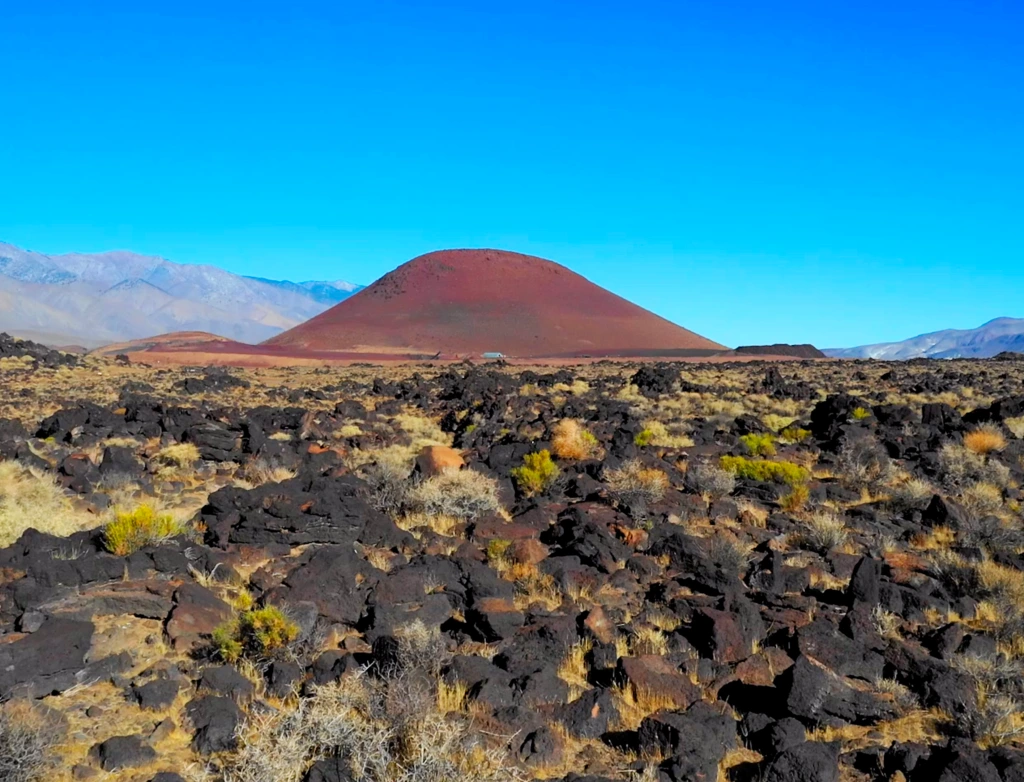

The Sea of Cortez is one of those freaks of geology, like the Sierra Nevada mountains or the volcanoes that rise from the ring of fire. These features appear because the earth is always in movement along the plates that comprise the earth’s crust. But let’s take a quick look at the Sea of Cortez today just to better understand this fascinating geological feature in today’s terms.

The Sea of Cortez today is under threat from our short time so far on the planet. Unfortunately, overfishing and pollution, including nitrogen-rich runoff from the Colorado River, which flows directly into the gulf, imperils wildlife. Nutrient flows can lead to a dramatic decrease in oxygen, depriving plants and animals of the life-giving gas. The potential extinction of the critically endangered vaquita (Phocoena sinus), represents one of the most urgent conservation crises in the region. The vaquita is the world’s most endangered marine cetacean, with estimates suggesting only a few individuals remain. This dire situation is primarily due to bycatch in illegal gillnets used for fishing another endangered species, the totoaba fish, whose swim bladder is highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine.

Habitat destruction is another growing concern, as mangroves, estuaries, and coral reefs, vital for the breeding and feeding of marine species, are increasingly destroyed to make way for tourism infrastructure and coastal development. Climate change intensifies these problems, with rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification threatening coral reefs and the broader ecosystem.

The birth of the Sea of Cortez also has an intriguing connection to a body of water hundreds of miles to the north—the Salton Sea. The Salton Sea, California’s largest lake, sits in the Salton Trough, an area geologists consider a “rift zone,” an extension of the same tectonic forces at work in the Gulf of California.

CALIFORNIA CURATED ART ON ETSY

Purchase stunning art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

It’s believed that over millions of years, these plate tectonic movements could potentially create a new ocean inlet, essentially turning the lower portion of California into a large island similar to Baja California. As the North American and Pacific Plates continue their slow-motion dance, the area around the Salton Sea may sink further, eventually linking with the Gulf of California. If this occurs, seawater could flood the basin, creating a new body of water akin to the Sea of Cortez. However, such a dramatic event is likely millions of years in the future—if it happens at all. Compellingly, the Salton Sea acts as a mirror, reflecting the past processes that led to the formation of the Sea of Cortez.

The Sea of Cortez stands at a crossroads: one dictated by the interplay of natural geological forces and human impacts. While tectonics may slowly carve out a new future, the choices humanity makes today will determine whether this natural wonder remains a thriving cradle of life or becomes an ecological shadow of its former self. By embracing sustainable practices and conservation efforts, there’s hope that the Sea of Cortez will continue to astonish and inspire for millennia to come.